|

|

|

|

|

Originally published (text and photos) in Zaghareet Magazine |

|

|

|

Theirs is an ancient and secretive culture that is, sadly, rapidly disintegrating in our all-to-intrusive

information-age society. But even if it is disappearing as a West Coast subculture, elements and influences of that Gypsy world remain. As the old structure falls apart I see, moving into mainstream culture, several

wide-ranging new Gypsy artists, each of them bringing a unique blend of concepts both ancient and uniquely ultra-modern. |

|

|

|

And Monique makes the most of our changing times as she takes her dance in a creative and uniquely

mystical direction. Romani background aside, she is also one of an increasing number, from a myriad of backgrounds, who are changing the definition, and more than that, the reality and very purpose of dance.

I recently had the opportunity to attend one of Monique's very occasional public performances. It was May 17, 2003 about fifty miles north of San Francisco, a large crowded hall in a bad

neighborhood. Several minutes before her scheduled performance, as she came through the door and into the colorful chaos that was Tribal Fest 3, I listened to the whispered comments around

me. "Looks like Darth Vader," someone said. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

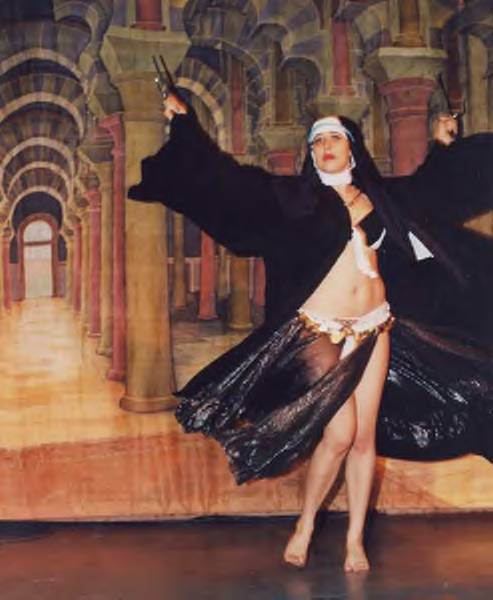

A very straight-laced

middle-aged woman nudged her husband, "Over there by the coin belts, is that a (Catholic) nun with swords?" Leaning with her back against the wall, a traditionally-garbed tribal

dancer muttered under her breath, "What the _ _ _ _?" On her way through the press of shoppers, audience members, and costumed dancers, Monique did attract more than usual attention.

In truth, she wasn't impersonating an outer space villain or a violent escapee from a convent. Her floor- length black robe and black and white head wrap were patterned after the ceremonial garb of the 11th century

mystic Cathars of France. And the two gleaming "swords" she carried were in fact seis (pronounced sighs), striking and throwing weapons that are still part of the arsenal of some Asian police

departments. |

|

|

|

All of this was Monique's creative visual transformation of the ancient God Inanna into a more

functionally contemporary persona. It was necessary that Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, and God of Love and War emanate, as much as possible, an aura of dignified spirituality, mysticism, and violent power.

The low-cut white silk blouse with flowing sleeves, and the diaphanous full dance skirt, now concealed by the robe, would at the right time, be a statement of divine sensuality. |

|

|

|

Monique is normally a very casual, and easy-to-get-along- with woman. But in performance she

becomes the deepest reality of her dance. And now, her mouth set in a firm expression, pale jade eyes fixed on some point in the distance, she seemed already in character

as Inanna, as she made her way through the |

|

|

|

|

|

crowd, oblivious to the many heads turned her way. |

|

|

|

Although not in any traditional sense, hers was to be a kind of trance dance.

It was not by accident or by casual choice that her performance was categorized as Sacred Dance. Hers was a unique and, some might say, even out of place performance in a festival highlighting America's best known Middle-Eastern tribal style dance troupes.

|

|

|

|

position as benevolent Queen of Heaven and Earth. |

|

|

|

This dance is one of several dance-art creations taken from Monique's upcoming film

The Making of Song of Salome. A film, and a spiritual saga; it's a history and a prophesy of the changing empowerment of women through the centuries. It is an unusual film, and definitely a necessary step in

Monique's new spiritual expression. And perhaps it's even a small step in the liberation and empowerment of dance itself in our modern world. |

|

|

|

To me, Inanna's Last Stand

is as classically archetypal as the waning moon. In it we see the last movements of a paradigm, and the very |

|

|

|

|

|

beginning of an ancient, but soon-to-be-completed, cycle. In her dance she is the pure-hearted feminine mystique ,

as it is brutally eclipsed by the onslaught of soulless aggression. Hers is a dance of ancient days, the end of the shapes behind mythology, and the beginning of our coldly rational and competitive world. |

|

|

|

|

|

I won't try to describe her performance except to say that it was prayerful, jubilant, war-like

(as silver blades flashed rhythmically) and tragic. And it was also somehow transcendent. This performance at Tribal Fest 3 was only an excerpt from the first act of a work-in-progress dance

drama (Monique Monet's up-coming film, The Making of Song of Salome) which attempts to show us the secret faces of the God Inanna as she emerges, now and again, from oblivion bringing soft promises of hope

and justice to our desperately repressive and mechanistically oppressed society |

|

|

|

Throughout my two years with Monique it has been abundantly apparent that spirituality and

mysticism are an on-going theme in her creations. And it's a theme I often see, to some extent or another, in the work of other neo-Romani artists. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am still pondering what this means. Perhaps it is the striving of an ancient but vanishing

people to reach back into their misty prehistoric beginnings, and lay hands on the real magic that is their source. |

|

|

(Since completing a Master's Degree at Southern Oregon University, Kay Seven has

worked as a technical writer, correspondent, and ghostwriter. She also spends much of her free time researching the sub-cultures of the world of contemporary dance. A resident of Ashland, Oregon, Ms. Seven studies privately with Monique Monet.) |

|

|

|

All rights reserved |

|

|