|

|

|

|

|

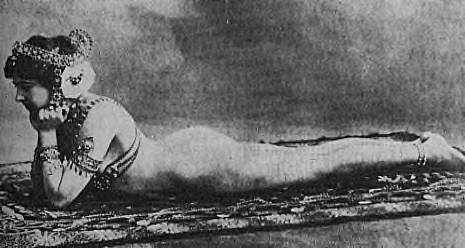

Dance of the Dawn

The Life and Death of Mata Hari

by Monique Monet |

|

|

|

|

|

Part II |

|

|

|

The thrill of "Gay Paris"

rapidly waned as Margaretha was forced from her fantasies to deal with the cruel reality of earning a living. She was very beautiful and found no difficulty obtaining work as an artists' model. But the excitement of working as a nude model quickly evaporated and

Margaretha found herself employed in a tiresomely boring and extremely low paid occupation. As was typical of her throughout her life she naturally gravitated from the

bizarre to the even more bizarre. Deciding that modeling was not for her, she chose for her next career that of circus bare-back rider. |

|

|

|

|

|

At Cirque Molier she diligently

studied horseback riding until the school's owner Ernest Molier commented to her that with her face and figure she would find more success as a dancer than as an equestrian. He was speaking her language and she quickly

decided that the idea of being a Paris dancer was much more attractive than that of circus performer |

|

|

|

Over the next few days she

modified Molier's advice to suit her own fantasy. Rather just another dancer, she decided to become the brightest star on the Paris dance scene. The plan swirled, almost ready-made, from her fertile imagination: |

|

|

|

She would combine her tourist-level knowledge of Javanese Temple dancing with her extensive

collection of Eastern jewelry and scarves. She would create an exotic personal history for herself. A story sure to catch the attention of a continent fascinated with all things Oriental. And as a sure fire

"hook", she decided to take maximum advantage |

|

|

|

|

|

of her physical attributes - - if it hadn't bothered her to pose nude for a room full of art students, it shouldn't be any more

difficult to swirl, unclad, across the theater stage. |

|

|

|

She had created everything she needed except a name. Margaretha Zelle MacLeod was not the name of a

sensuous, priestess of le Danse Oriental. After long and careful thought if finally came to her - - the perfect name! Overnight the desperate and confused young Dutch woman disappeared and in her place stood the

powerful and alluring Mata Hari. Her new name a Malaysian term which translated as "Eye of the Day," (referring to the sun). |

|

|

|

Her first two

performances were for charity benefits. The surprised audiences were not expecting a nude Oriental temple dancer. But their surprise quickly gave way to amazed appreciation. In a matter of weeks after her first charity

performance, Mata Hari was featured at the |

|

|

|

Parisian society event of the year, the opening of Monsieur Guimet's Museum of Oriental Art. |

|

|

|

Everyone was talking

about the new dance sensation, the innocent native girl, and her traditional and chaste yet sensuous dance. On the night of the museum's opening all tickets had long ago been sold. And a room full of eager gentlemen and

ladies awaited this daring exhibit of foreign culture. |

|

|

|

|

|

The second floor of the museum had been transformed into an Indian temple. High columns were

twined with fragrant jasmine flowers. Erotic Hindu statuary lined the walls. While an unseen orchestra played Indian music, four girls in black togas escorted the scantily-clad Mata Hari on stage. As the

audience leaned forward in their seats, the dance bagan. |

|

|

|

|

Mata Hari's ancient traditional temple dances

were, of course, all of her own invention. First, she performed a dance called Poem of the Princess and The Magic Flower. Audience member, Frances Keyzer, an English correspondent, described Mata Hari's first dance.

"She stands before us as a graceful young girl, her eyes fixed upon the statue of Siva at the end of the room. Her olive skin blends with the curious jewels in their dead

gold settings, |

|

|

|

|

|

and is accentuated by the colorful sarong around her waist. In her hand she held a passion flower, and she danced to it with all

the gladness of her sunny nature. But the flower was enchanted, and under its charm she loses command of herself and slowly unwinds the sarong. As the veil drops to the ground, consciousness returns. She is ashamed and

covers her face with her hands. |

|

|

|

"Nothing inanimate will render the emotion conveyed by the performer, nor the color and harmony of

the Eastern figure. It was a tropical plant in all its freshness, transplanted to a Northern soil. The Parisians who witnessed the performance were struck with the unconscious art of the dancer, and with the

intelligence and refinement she displayed." |

|

|

|

After a couple more comparably tame numbers, Mata Hari was ready for her grand finale, The Invocation of

Siva. |

|

|

|

Parisian theater critic Edouard Lepage describes this 1905 show stopper. "Mata Hari,

The Eye of the Day, the Glorious Sun, the sacred Bayadere who until now only the priests and the gods can claim to have seen in the nude, was tall and slim and supple like the unrolled serpent which is

hypnotized by the snake charmer's flute. Her flexible body at times becomes one with the undulating flames, to stiffen suddenly in the middle of her contortions, like the flaming blade of the kriss.

"Then, with a brutal gesture, Mata Hari rips off her jewels, tears her veils. She throws away the ornaments that cover her breasts. And, naked, her body seems to lengthen way up

into theshadows! Her outstretched arms lift her on to the very tip of her toes; she staggers, beats the empty air with her arms, whips the imperturbable night with her long heavy hair . . . . and falls to

the ground." |

|

|

|

|

|

The entertainment reporter for the newspaper La Presse

also describes her wild last number of the evening. "Mata Hari does not only act with her feet, her arms, eyes, mouth, and crimson fingernails. Mata Hari, unhampered by any clothes, plays with her whole body. And then, when the gods remain unmoved by the offer of her beauty and youth, she offers them her love, her chastity - - and one by one her veils, symbols of feminine honor, fall at the feet of the god. But Siva wants even more - - one more veil, a mere nothing - - and erect in her proud and victorious nudity, she offers the god the passion which burns in her. Finally the priestess, gasping for breath, sinks down at the feet of the god, while her servant girls, amidst thunderous bravos, cover her with a golden sheet."

|

|

|

|

|

|

That same year Mata Hari danced in all the most exclusive

salons of Paris. She performed repeatedly at the Trocadero Theatre, where arrangements had been made to represent her in a setting that approximated as closely as possible the atmosphere of The

Guimet Museum. She danced three times at the home of multi-millionaire socialite Baron Henri de Rothschild - - always among oriental carpets, palm trees, flowers, and incense burners. From

unknown artists' model, Margaretha Zelle had become the toast of Paris society in less than six months. Her popularity was a |

|

|

|

|

|

timely blend of Europe's obsession with everything Oriental, her own natural charisma, and an aura of innocence that somehow made

her sensuous nude performances acceptable to a wide range of audiences. Paris, in the early years of the twentieth century, was not a nation devoid of restrictions. Other dancers who dared to perform unclad were

routinely arrested and sent to jail. But somehow Mata Hari, the spiritual Brahmin princess, remained above the law. A couple of years later, at the zenith of her career, she was delighted to

discover that in most people's opinions, she had eclipsed even the world famous superstar Isadora Duncan. The popular magazine La Vie Parisienne

said, "In the earlier season Miss Duncan reincarnated ancient Greece. With the music of Beethoven, Schumann, Gluck, and Mozart she restored the pagan dance movements. This season we have Mata Hari. She is Indian, with an English mother and a Dutch father, all of which is a little complicated. Yet she is Indian. Miss Duncan apparently danced with only her feet and her arms showing, while Mata Hari is entirely naked, with only some jewels and a piece of cloth around her hips and legs. She is charming - - a rather big mouth, and a pair of breasts which make many a spectator, too heavily provided for comfort, sigh with envy."

The English correspondent, Frances Keyzer, put it more succinctly. "Miss Duncan is Vestal and Mata Hari is Venus." Neue Weiner Journal

spelled it out most blatantly "Isadora is dead! Long live Mata Hari!" |

|

|

|

Her celebrity status didn't end at the stage door. And, as with everything else about her new

fantastic existence, she enjoyed her fame to the fullest. Mata Hari found herself constantly pursued by wealthy businessman, politicians, and high ranking military men. (It was her attraction to the latter

which ultimately proved her downfall.) Although she never remarried after Colonel MacLeod, she was happy to bask in the admiration of a series of suitors willing to provide her

with lavish gifts and extended stays in luxurious chateaus. Year after year passed and still Mata Hari remained the Madonna of the Paris dance world. |

|

|

|