|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

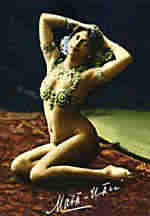

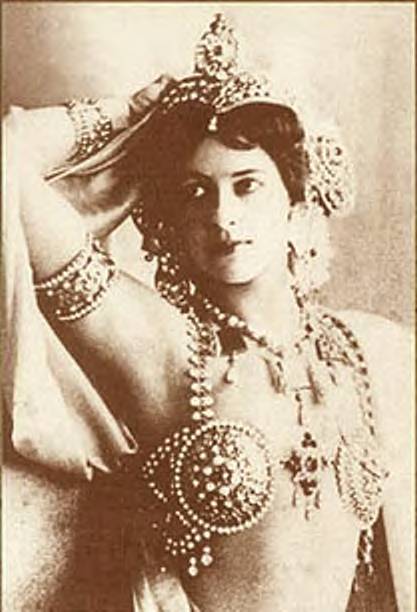

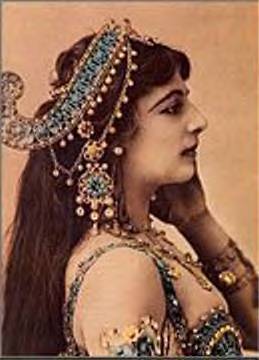

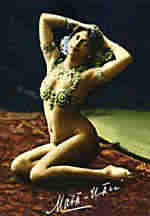

Dance of the Dawn

The Life and Death of Mata Hari by Monique Monet

|

|

|

(Originally published in Jareeda Magazine) |

|

|

|

Part I |

|

|

|

|

It was the turn of the (last) century that le Danse Oriental

captured the interest of the Western world. The poems of Colette, the novels of Flaubert, and the "Orientalist" paintings of Gerome all wetted the Western appetite for more of the mysterious, exotic and sensuous, Dance of the East

. When Little Egypt

performed at the 1893 Chicago Expo her audiences were surprised, often shocked--but always filled to capacity. Another of the "founding mothers" of oriental dance in the

West rocketed to stardom, only to fall victim to the cruelty and deceit of men at war. She, and her reputation, were senseless casualties; causing her to be remembered today not as a dancer but as a

notorious spy. |

|

|

|

|

|

As she confided to her

friend, the artist Piet van der Hem, " I never could dance well. People came to see me because I was the first who dared to show myself naked to the public." The dramatic movements and gestures of her

"sacred dance" were the products of her fruitful imagination. In fact, all things considered, Mata Hari was much more an imaginary being than she was a real woman. |

|

|

|

The basic flesh and

blood raw materials from which Mata Hari constructed her being were sadly mundane: Of Dutch heritage, she was born Margaretha Zelle in Leewarden, Holland, August 7, 1876. |

|

|

|

Margaretha came

naturally by her fertile imagination. Her father, Adam Zelle, a Leewarden hat shop owner, like to represent himself to his fellow villagers as a duke -- the last of an ancient aristocratic family. And as long as his

finances held out he did his best to dress and act the part. |

|

|

|

|

|

As the

daughter of a "Duke", the child Margaretha attended private school, arriving in her own shinny red goat-drawn cart. Her classmates might of been happily impressed by this extravagance, but they and

their parents were clearly aware that Margaretha and her family were no more of royal blood than the baker or blacksmith. It was simply an accepted fact that Adam Zelle enjoyed pretending to be a

"duke" and aside from that one eccentricity was a honest shopkeeper and a good neighbor. The family troubles began when her father's aristocratic airs began to drastically exceed his shopkeepers income. Over- spending eroded his business

until the |

|

|

|

|

humiliated Adam Zelle was forced to move his family into an unaristocratic little house by the rail road track, while he accepted

a job as a traveling salesman. Deprived of her shinny red goat cart, thirteen-year-old Margaretha had to walk to her classes at the public school. |

|

|

|

With the passing of

time Margaretha's home life only grew worse. Her father was never home anymore. Her mother died. And sixteen-year-old Margaretha was sent to live with her godfather while she studied to be a kindergarten teacher

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After a

scandal at the teacher's college involving Margaretha and the headmaster, she gave up thoughts of teaching and moved to The Hague to live with her uncle. A beautiful seaside city, The Hague abounded with

cultural and recreational opportunities. But in spite of her surroundings the now exotically beautiful Margaretha found herself lonely and confused. She knew she couldn't live with her uncle forever but she

had no idea of how to earn her own living. On March of 1895 an ad in the newspaper caught her attention: "Officer on home leave from Dutch East Indies would like to meet girl

of pleasant character -- object matrimony." Filtered |

|

|

|

through her imagination, the few terse words became a golden gateway to romance, adventure -- and of course

the security she was so desperate to find. |

|

|

|

In reality the ad was nothing but a practical joke placed in the paper by friends

of the officer mentioned. He was thirty-eight year old captain Rudolph MacLeod. A tough, career military man who had worked his way up through the ranks. It would be difficult to imagine a person anymore the

opposite of the pampered daydreaming teenage Margaretha. |

|

|

|

|

|

His grumbling about

the annoyance of the phony ad stopped when he received Margaretha's letter and photograph. He contacted her and they made plans to meet at the Amsterdam Museum. Apparently it was a case of opposites attracting, he

proposed to her six days after their first meeting and she accepted. |

|

|

|

Margaretha

had longed for a life of exotic adventure, and her wishes were certainly fulfilled. At age twenty she found herself halfway around the world, living in the village of Ambarawa on the Indonesia Island of

Java; wife of a rugged military man and mother of an infant son. Several peaceful years passed. Captain MacLeod became Major MacLeod, as he busied himself protecting European

interests in Indonesia. Margaretha, vivacious and colorful, found herself warmly welcomed into the Dutch military community. She had another child, a daughter, and seemed comfortable with her life as a

homemaker in the exotic tropics. |

|

|

|

|

|

But fate had other

plans for her. Abruptly, at the turn of the century, the idyllic life in her new world began to fall apart. Her son was poisoned. Rumor had it that the killing was revenge for Captain MacLeod's involvement with a

married woman. She blamed him for her son's death, and he guiltily sought comfort with other women and alcohol. Brokenhearted and rundown with anxiety, Margaretha contracted typhoid fever. |

|

|

|

In a desperate attempt to save their relationship, MacLeod resigned from the army and he, Margaretha, and

little Non, their daughter, returned to Holland. But the return home offered no benefit to their rapidly deteriorating marriage. MacLeod continued with alcohol and other women. And in 1902 Margaretha filed for divorce

sighting adultery, and "brute cruelty". |

|

|

|

MacLeod had a

comfortable income from his army retirement. But Margaretha quickly discovered he had not the slightest intention of sharing even a penny of his income after she and her daughter moved out into a place of their own.

Unemployed, unskilled and with a child to support, Margaretha found herself in a desperate situation. She begged her ex-husband for help, and wrote pleading letters to relatives, but to no avail. With no money for rent

and no food in the cupboard, Margaretha did as she often did when she found herself with her back against the wall -- she slipped into the bright and magical world of imagination. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

She dreamed

of making a fortune as an actress. She pondered a career as a bareback rider in the circus. And most of all, she contemplated the land of art and beauty where she had always longed to live -- Paris.

As her real life situation moved from difficult to impossible, she made the bold decision to leap into her fantasies. Placing her daughter with relatives, Margaretha used her last few dollars to

buy a ticket to Paris . |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part II |

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: Capek, Carel, Letters from Holland, London: Faber & Faber, 1933. Encyclopedia Britannica,

Mata Hari, 15th Addition, Chicago, 1994. Howe, Russell Warren, Mata Hari, The True Story, Dodd, Mead, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and Company, New York, 1986.Newman, Benard, Inquest on Mata Hari, London: R. Hale, 1956 . Ostrovsky, Erika, Eye of Dawn, The Rise and Fall of Mata Hari, Macmillan Publishing Co.,

Inc. New York, 1978.Svetloff, Valerien, The Execution of Mata Hari, The Dancing

Times (London), Nov. 1927. |

|

|

|

Waagenaar, Sam, Mata Hari, New York: Appleton-Century, 1965. |

|

|

All rights reserved |

|

|